I want to be happy with my voice and its foolish joys

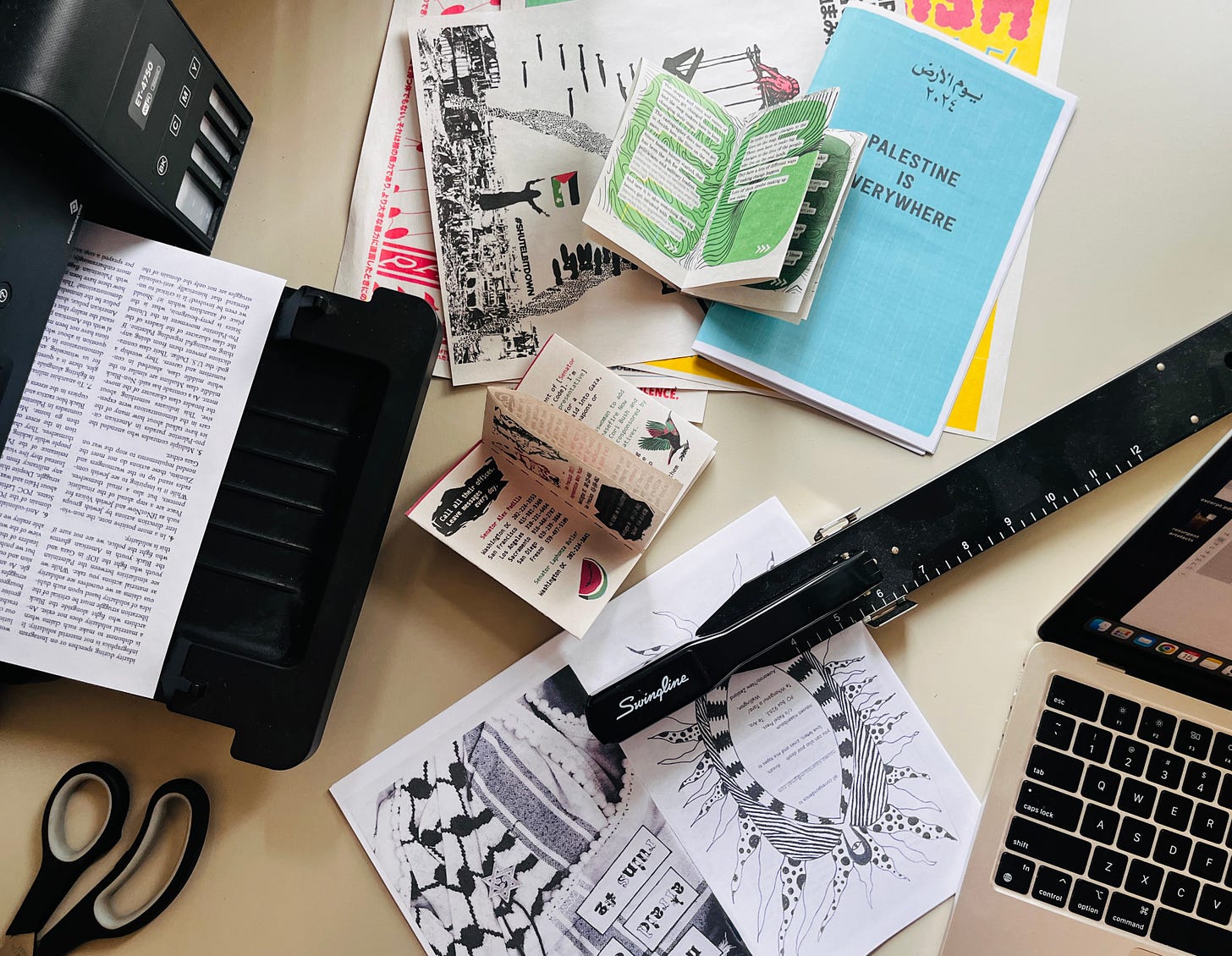

#20 - marginalia from the PhD halfway point

As the subtitle has announced, I’m at the halfway point in my PhD (waow!) and still plodding along (three years in, three years to go), wrestling through the specificities of each line of work I’m entangled in, and making choices along the way.

I identify with Moten’s fugitive academic, and I love the dedicated space that academics get to think in, write from, and negotiate through, even as it is fraught with all its bells and whistles, its shadings of violence, its unironic over-idealization.

So what to do? I’m not sure, but when I do choose to write, I choose my own way and read the cards as they fall.

Last month, for a summer course I’m taking, I chose to respond to Fady Joudah’s astounding piece, “A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation: Thirteen Maqams for an Afterlife”.

The assignment was a traditional reading summary that would open space for class discussion with peers. A reading summary asks for a summary, asks for engagement and interpretation, and asks for questions.

I think my reading response was a process of writing through my thinking about what this format of writing could do. How can I meet the strength of the piece I read with my own feelings? What language can do it (if not justice) tender, attentive and earnest? Can the writing be shared beyond the space of the classroom? Can it move and touch other people in other spaces?

There aren’t right answers to this question (although there may be wrong ones), and I think the next half of my PhD will only give me more material to chew on in trying to wrestle language into the shapes I ask of it, for the things I want to say and the places I want it to go.

My reading response to Fady Joudah:

The arabic maqam is a system of scales, melodic modes that form the foundation of Arabic music. The Islamic maqām is a spiritual stage that marks the path to be followed by Sufis. The word “maqam” means place, position, or location. Maqam also literally means “ascent”.

In A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation, Fady Joudah takes up the maqam as lament, referencing the affective power of the sonic and the textual to frame his thirteen-part text. Beginning and ending with the final words of Hiba Abu Nada, one a poem, and the other a social media post, Joudah works through the paradoxical performance of language as a spoken and textual archive of unspeakable, unrepresentable loss. The essay moves backward and forward in time with each maqam, from 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, 2017’s Hurricane Harvey to the perpetual present of post-October 2023. In each maqam, some scrap of language is returned to: marginalia, correspondence, poetry, proverb, the news. In each maqam, Joudah grapples with meaning and senselessness in the context of annihilation, tracing the psychosis of “Palestine in English” that afflicts “the American and Israeli vernacular”, how the way Palestine, when spoken, warps the colonizer’s language.

Joudah revisits old texts and languages as archive, roving as the speaker between personal events to build a position. maqam. The “I” is formed into an archive that speaks of the present through the past, an “I” that witnesses “my collective Palestinian death”, a meeting ground of words (descriptive, interrogative and emphatic) reanimated for the right now. On one hand, there is a reanimation through media which Joudah observes with critical suspicion. Language can become “relatable sound, relevant corpus” for the neoliberal market; the “I” can become “a vessel for the outpouring of empathy” that clouds the violence of the Western free world. On the other hand, there is reanimation through the maqam. Joudah invokes Palestinian writers, Hussein Barghouti, Mahmoud Darwish, Ghassan Zaqtan together with Hiba Abu Nada, producing found poetry from Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby in maqam 9 to acknowledge that the structures of violence that bear onto Black and Brown bodies alike are the same. Darwish’s poem “The ‘Red Indian’s’ Penultimate Speech to the White Man,” expands the address of the text from one genocide to another. Old language can be used to condemn the present because the violence then and now is not much different. Relatable sound in this context also speaks to shared oppressions, to interconnected experiences of violence across time and space.

More importantly, language not only speaks of loss, but invoked in this text, is the site of loss. In maqam 11, Joudah speaks of the proverb, “To die along with a collective is a mercy”, offering a definition and context for its meaning, before immediately exploding its wisdom through a confession: collective death when experienced, is unspeakable. If “for this Palestinian proverb to become a Palestinian reality devoid of metaphor is a definition of genocide”, if the voiding of metaphor marks the definition of genocide, then genocide is where representation cannot happen. Language breaks down totally. These are things that are untranslatable into language: death by annihilation; a life worse than death; what it means to be Palestinian.

The thirteen maqams as melodic modes also invite the aural into the archive of language presented to us in written text that writes of their obliteration. Abu Nada’s last poem houses the voice of God welling up from the inner “I”. Words are what we send with the dead to the afterlife through speaking. The destruction of the sonic archive of language begins in Joudah’s moment of silence in maqam 3 and culminates in his grieving over the assassination of Wael Dahdouh’s family in maqam 12. The assassination meant to break Dahdouh’s voice, and by extension, to extinguish the voices of those who listened to him is one in a long series of silencing gestures. The archive reminds us that this targeted violence is cyclical—the death of Shireen Abu Akleh is a sonic void we had not yet finished grieving. Annihilation is a sound that destroys other sounds.

Even so, “I want to be happy with my voice and its foolish joys,” Joudah writes in maqam 13. If parts of the self that get buried in books, resurfacing as marginalia in the future, become “a version of our afterlife”, then Joudah’s writing is “a marginalia of my soul” that becomes a version of an afterlife for the inconceivable, unspeakable violence that Israel has wrought on Palestinians. The afterlife is the archive is the sound of lament, grief, rage and desire as marginalia, coalescing in an intertextual, sonic place: maqam. “How different was the beginning?” Joudah asks, and the archive of the text answers, “It was this way from the beginning.” “What will I tell my children? What will you tell yours?” Joudah asks, and the text does not answer. Silence resounds.

How do we ensure the archive reanimated does not produce relatable sound that echoes without troubling the violent structures of the present? Conversely, how do we animate an archive against the enactment of violence? How can an archive dismantle a structure?’ Is it possible to hear the sonic archive in a time of annihilation? How/can archives prevent present and future annihilation?